solo projects

Aluminium

![]()

Silver from Clay

Although aluminium is the Earth’s most abundant metallic element, and the third most common element in the Earth’s crust after oxygen and silicon it took until the early 19th Century before it was isolated and put to the ubiquitous use we see today.

REALTOY ‘INTERNATIONAL’ & BOEING JUMBO JET

Zinc & Aluminium die cast metal, manufactured in China, bought in Allendale.

In 1808 Humphry Davy had the task of naming it, and it took a while for him to settle on how it should be spelt, flopping between an –ium, then an -um and then back again. The naming didn’t make much difference up until the mid 1850’s, as only minute quantities, at substantial cost had ever been extracted from bauxite ore.

In 1855 it was still so rare and valuable in its pure form, that at the Paris Exhibition of that year, Sainte-Claire Deville exhibited a small amount of aluminium next to the crown jewels. This caught the eye of Napoleon III, the last monarch of France, as something of potential military application and he was persuaded to fund further research into extraction. The first thing that was made for him, however, was a rattle for his baby son, then the more war-like aluminium breastplate and finally some soup spoons. An army does of course march on its stomach, as Napoeon III’s uncle said.

In 1886, an inexpensive way of obtaining this ‘silver from clay’ was found independently by Charles Martin Hall in Ohio, and the Parisian Paul Héoult. By 1888 the Hall was funded to set up the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, today known as Alcoa, to exploit the Hall- Héoult electrolytic process still used today. In an 1893 advertisement for his new electrolytic process, he spelt it with an –um, despite continuing to use the ‘European’ spelling –ium when applying for patents until after the turn of the century.

In 1887, an Austrian chemist Karl Bayer, invented a way of producing alumina (aluminium oxide), which is smelted for use in the Hall- Héoult process for aluminium metal production. The modern field of hydrometallurgy was born, aluminium prices dropped dramatically, and its use spread. The United States came to dominate aluminium production, and the American press and public, who were using Hall’s –um spelling, led to the American Chemical Society officially reverted the spelling back to aluminum to reflect this in 1925.

A year later, the Ford Motor company produced the Ford Trimotor, one of the first all-metal airplanes more commonly known as the ‘Tin Goose’. Its wings were made from a corrugated aluminium alloy known, at the time, as duralumin, and was indiciative of the move towards flying ‘tin’ cans.

As aluminium production increased, it replaced tin foil in food preperation, which had the side effect of imparting a ‘tinny’ taste and tin cans (made of tinplate steel), on account of its declining price and malleability in the manufacturing process. Its slighty cumbersome (and unresolved) name, together with its role as a direct replacement for several common products, led people to continue to say tin long after it was dropped in the manufacture of those goods.

The Letter of the Law

Despite the different spellings of the element, and the use of misnomers besides, by the time the United States entered the Second World War on the side of the Allies, Napoleon’s hunch of its value in military applications had proved correct. With Alcoa producing aluminum for U.S. and Allied warplanes, the only invaders to land on the American mainland came with the purpose of "harming as much as possible aluminum production in the United States."

To this end, Nazi submarines landed eight somewhat hapless saboteurs - four in Florida and four on Long Island to blow up Alcoa’s plants. All eight had previously spent time in America. One had been stayed for twenty years, and another was a naturalized American citizen, living there from the age of five. All had returned to Germany, and came back to the US with a supply of explosives and $90,000 cash.

In ‘Saboteurs: The Nazi Raid on America’ Michael Dobbs describes how, free from Germany's wartime austerity, they began spending their cash on food, clothes, drink, women, and, even in one case, a new car. As some of the saboteurs got back in touch with friends, relatives, and former girlfriends, one of the saboteurs, George Dasch, rather helpfully, got in touch with the FBI. Within two weeks they were all in FBI custody, and tried by a military tribunal they were found guilty.

They were denied rights to habeas corpus, which had not been suspended since the Civil War. Six of the eight were quickly executed by electrocution, whilst Dasch and another informer were imprisoned for the war's duration and eventually returned to Germany.

If this sounds somewhat familiar to more recent events, the Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist remarks quoted in the book from a 1999 speech may shed some light on the matter: "While we would not want to subscribe to the full sweep of the Latin maxim INTER ARMA ENIM SILENT LEGIS (roughly, in a time of war, the laws are silent), perhaps we can accept the proposition that, though the laws are not silent in wartime, they will speak with a somewhat different voice".

The aluminium saboteurs case formed the legal precedent for the trying of Guantanamo prisoners in military tribunals.

Property of the U.S. Government

In U.S prisons and correctional facilities where the rights of habeas corpus do apply, a captive labour force produces around16 million automotive license plates each year. The work begins with a blank sheet of aluminium, and is a repetitive and detailed task involving the operation of heavy equipment as part of a prison industries programme developed to “reduce recidivism by teaching prisoners a skill while at the same time producing low cost manufactured goods.” These schemes allow the ‘production facilities’ to manufacture and sell items at what has been described as a ‘nominal cost’, with the proviso that they have to compete in the ‘free market’ economy and sell their goods inter-state and overseas.

Forty five states use prisoners to manufacture their plates, though this particular one, celebrating the turn of the century Alaskan/Klondike gold rush, is more likely to have been made by the Irwin-Hodson Company of Portland, Ore, in 2004.

I bought it at a Hexham car-boot fair in 2007 from a woman whose father emigrated to Moosejaw, Saskatchewan. She brings back ‘Canadian stuff’ when she visits him for her regular stall, and also gets him to airmail packages over when supplies run low.

Saskatchewan still has a gold mining industry, and also produces about a third of the world's uranium but is mainly known for its agriculture, producing almost half of Canada’s grain. This is reflected in its usual license plate, which depicts three stalks of wheat and bears the slogan "Land of Living Skies."

The town’s name is thought to come from the Cree word moosegaw meaning "warm breezes", and various geographical factors result in the area having a high number of cloudless days, making it a prime site for training pilots. In 1940, the Royal Canadian Air Force established a facility there, and trained pilots for Allied bombing campaigns in mainland Europe.

Some of the missions were aimed at crippling Germany’s industrial production base, run by a conglomerate of German chemical industries called IG Farben that formed the financial core of the Nazi regime. This included a company called Bayer, set up by the father of Karl Bayer, the discoverer of the alumina smelting process that had helped usher in the new era of cheap aluminium and the possibility of industrial warfare.

At the end of the war, the U.S deployed Operation Paperclip, removing over a thousand scientists from Germany, including Werner Von Braun, the father of the V2 rocket. Many of the German scientists, committed Nazi’s among them, would play a leading role in the development of ever more powerful rockets in America’s military programme, which would also help them hitch a ride to the Moon during the Cold War space race.

Here I Am Floating In My Tin Can - Space Oddity

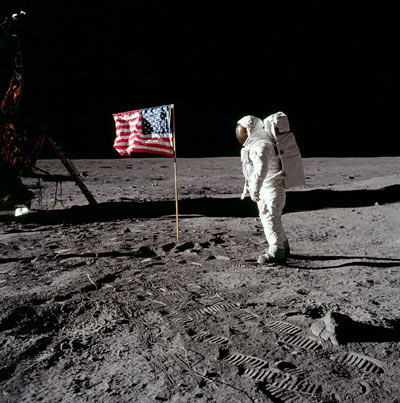

The three astronauts who blasted off on the back of a Saturn V rocket on the 16th July 1969, would descend onto the moon’s surface in the Lunar Module – a buglike craft containing a thin aluminum skin encased by a Mylar thermal-micrometeorite shield This tin can was so thin that Buzz Aldrin was quoted as saying, I believe I could have poked a pencil through it” and workers at the Grumman factory caused damage to it when they dropped tools inside. It was, it seems however, purportedly designed well enough that on the 20th July 1969, the flag of the United States was planted onto the lunar surface.

Earlier that year, in preparation for this event, NASA’s Committee on Symbolic Activities for the First Lunar Landing was set the task of working out what kind of flag would ‘fly’.

The flag was to be a symbolic activity, as the United Nations Treaty on Outer Space precluded any territorial claim. Indeed, the Committee even discussed placing a United Nation’s flag, or miniature flags of United Nation member countries on the moon.

Whatever they chose, however, “the aim of the whole committee was to make it clear that, regardless of the symbol chosen, the United States had landed on the moon first.”(1)

In the event, Congress passed a law that decreed “...the flag of the United States, and no other flag, shall be implanted or otherwise placed on the surface of the moon, or on the surface of any planet, by members of the crew of any spacecraft ... as part of any mission ... the funds for which are provided entirely by the Government of the United States."

When looking at ‘Old Glory’ finally planted on the moon, Buzz Aldrin sensed an "almost mystical unification of all people in the world at that moment."

![]()

The Art of Flying

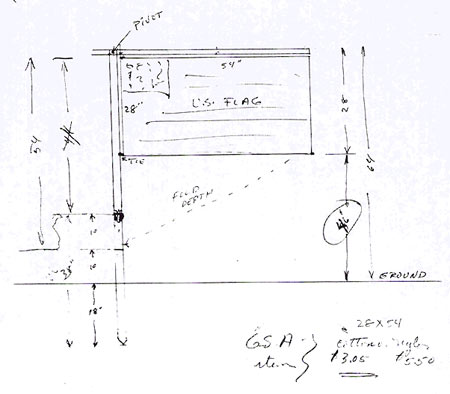

The mechanics of ‘flying’ the flag on a windless moon was looked at in the three months before the mission took place. The U.S flag eventually used cost $5.50 and it was braced, together with its aluminium assembly rods and heat shroud to the outer ladders as it was a fairly last minute addition and there wasn’t much room inside the lunar module. The flag assembly, made of a two-part aluminium pole, included a horizontal telescopic crossbar, designed to hang the flag off.

Kinzler's preliminary sketch for the Lunar Flag Assembly (NASA website)

One of the more famous conspiracy theories that the moon landings (or at least the first one) were faked, comes in the form of the ‘flag fluttering in the breeze’ theory.

The flag-waving that occurred as it was being manoeuvred into position was, on balance, probably due less to the fact that it was all made up in a television studio in the manner of Capricorn One, and more likely a combination of the restricted mobility of the astronauts and the compacted nature of the lunar soil. This meant that the astronauts had to wiggle it into place and balance it into a standing position.

It took ten minutes to complete the illusion that it was more or less flying as it would do on the planet they had departed four days earlier. I suppose if they hadn’t gone to all that trouble, then it would have looked rather like a limp symbolic act.

Spotting A Flag on the Moon

I've come across several postings asking if 'Old Glory' is still fluttering in the breeze, and whether or not it can be photographed. The flag is a standard 4-foot flag, and would need an optical telescope 200 metres in diameter to spot it. The closest we have is the W. M. Keck telescope in Hawaii, which is 'only' 10 metres in diameter. Even the Hubble telescope, orbiting the Earth 600 kilometres away would only see the flag as a single pixel.

Buzz Aldrin’s last glimpse of the flag came as the Lunar Module departed the moon at 1:54 p.m. EDT on July 21st. Later, he spoke of the fact that "There was no time to sightsee. I was concentrating intently on the computers, and Neil was studying the attitude indicator, but I looked up long enough to see the flag fall over.”

So, perhaps the current crop of Japanese, Chinese and American probes and future taikonauts will be able to beam back pictures to remind him where he left it.

This model wasn't bought from a car-boot sale but I borrowed it from here. It’s made with golden-coloured sweet wrappers for the shroud, which are probably made from an aluminium and mylar material much like the actual lunar module. It’s a much more elaborate affair than the lunar landscape that I made as a child which was thrown away after a mouse had eaten all of the papier-mâché hills and just left a tattered, hollow aluminium foil surface.

Space Cooking

Back on the real moon, and before all the flag-waving, Armstrong and Aldrin also found time to carry out some experiments. One of these involved hanging out a roll of aluminium foil, similar to domestic cooking foil, though I don’t think they bought it in the local Sears department as they reportedly did with the Stars and Stripes.

The shaft was ‘emplaced’ with some difficulty onto the surface and the foil unrolled to face the sun, hanging a bit like the vexillum standards carried by soldiers of the Roman Empire. To stop the astronauts getting confused about which side should point where, there was a handy bit of writing on one side marked ‘shadow’. Once in place, it was used to trap the electrically charged particles that the sun sends out into space known as the solar wind.

The solar wind doesn’t make it through the Earth’s magnetic field, except in the upper atmosphere at the poles that lead to the spectacular lightshows of the Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis. On the moon, however, with very little atmosphere and without the ‘protection’ of the Earth’s magnetic field for most of each month, solar wind particles reach the surface at speeds of approximately 450 kilometres per second.

This ‘space weather’ varies, and indeed you can receive a fresh update every ten minutes brought to you from the ACE spacecraft that is about one one-hundredth of the way from the Earth to the Sun. From there it takes about 1 hour to affect our geomagnetic activity. Whilst I was writing this, the solar wind speed was 417.9 km/sec with a density of 1.6 protons per cubic centimeter. I think this basically translates as averagely gusty.

Lights on for the Territories

The first solar wind experiment had a very short cooking time, but several other Apollo missions continued with these experiments, leaving the foil out for as long as 45 hours before being brought back to Earth for examination.

It was found that the 5% of the solar wind that was not made from gaseous plasma contained isotopes of light noble gases, of amongst others helium, argon, and neon. The isotope helium-3, rare on Earth but fairly abundant on the moon from the solar wind, is now seen as a potential future replacement for fossil fuels and seen as a factor in China, Russia and United States interest in setting up bases on the moon. China, who are now about to map the moon with an orbital craft, is planning its first unmanned lunar surface sampling mission in about a decade.

China’s chief lunar scientists, Ouyang Ziyuan’s recently stated in a Chinese nespaper "We will provide the most reliable report on helium-3 to mankind…Whoever first conquers the moon will benefit first."

Almost forty years since the U.S flag was planted on the moon, and aluminum foil-wrapped helium-3 made its way back to Earth, it will return, with a different name, and possibly from a different country. Whatever the outcome, I still won’t be able to work out how to rid my American made word processing program of its insistence that aluminium as a word does not exist.