solo projects

If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing To Fear

23rd August - 6th September

Curated by Michelle Rheeston-Humphreys

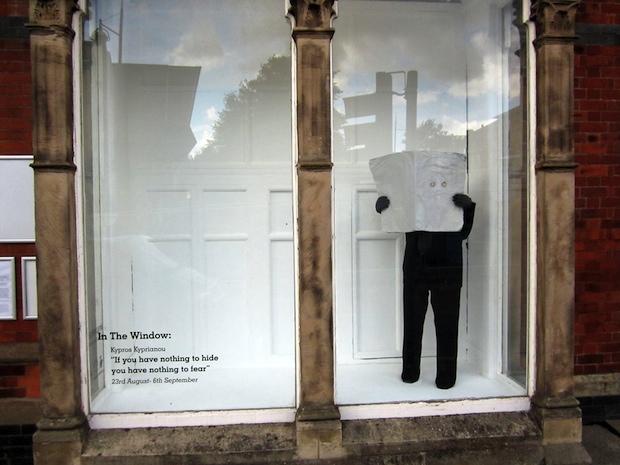

If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing To Fear: Installation view Airspace In The Window Kypros Kyprianou 2014

If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing To Fear: Installation view Airspace In The Window Kypros Kyprianou 2014

'f You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing to Fear' takes its title from a phrase attributed to everyone from George Orwell to Joseph Goebbels. It has been repeated more recently by William Hague, framed as an assurance over intelligence agencies currently harvesting vast amounts of online-based communication.

The piece is a comic book rendering of this surveillance albeit from a different spy era - the Cold War. It takes the form of a life sized figure, stood as if reading a newspaper with holes cut out for its eyes. It is fashioned using rudimentary materials – papier-mâché, ping pong balls and heavily applied paint. There is little of substance to the figure – there are no arms attached to the hands, and the ping pong ball eyes are have marker pen dots on them, slightly glowing to complete the slipshod illusion.

To the casual passer-by it might look at first look convincing. On closer inspection it is a flimsier construct. But for 2 weeks, it is always there, night and day, watching.

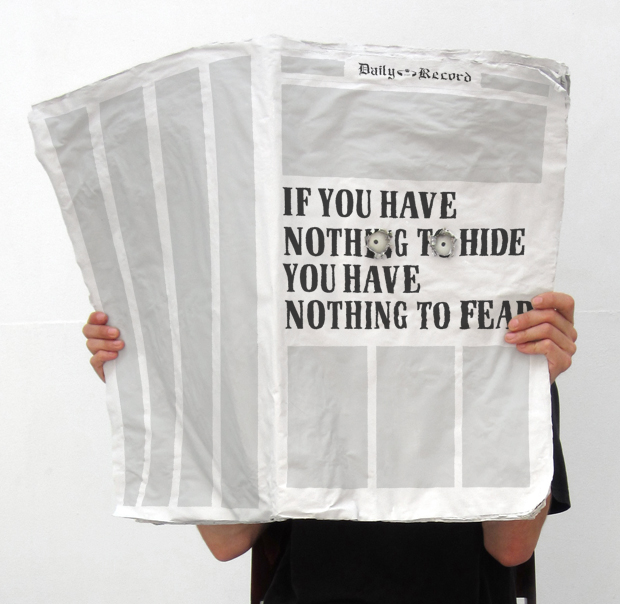

If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing To Fear (detail): Installation view Airspace In The Window Kypros Kyprianou 2014

If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing To Fear (detail): Installation view Airspace In The Window Kypros Kyprianou 2014

“If You Have Nothing To Hide You Have Nothing to Fear” is a phrase attributed to everyone from Joseph Goebbels to George Orwell. It was repeated more recently by William Hague to justify the UK’s intelligence agencies harvesting of digital communication - though I am not sure whether Hague was quoting Goebells or Orwell when he repeated it to deliver his reassurance.

In 2009, another student of Orwell, Justin Gawronski, a 17-year-old American who had been reading “Nineteen Eighty Four” on his Amazon Kindle for his summer assignment lost all his digital annotations when the file vanished from his device. “They didn’t just take a book back, they stole my work,” he said.

The irony of Amazon remotely deleting Kindle copies of Orwell’s book over a copyright violation was not lost on many commentators - in Orwell’s book government censors destroy news articles embarrassing to Big Brother, sending them down an incineration “memory hole.”

Unless Gawronski was jotting down the overthrow of government in the margins, I doubt he had anything to hide, and the publicity generated from the incident would surely mean he had nothing to fear over handing in his assignment late.

Transposing this scenario from digital to physical space would entail something along the lines of a company representative breaks into Gawronski’s house, destroying the book and notes, then leaving an explanatory missive.

This scenario would have caused a consternation in many sections of the press. Yet, when David Miranda, the partner of journalist Glenn Greenwald was detained at Heathrow airport and made to hand over his laptop and encryption keys, reaction was rather more subdued. Greenwald had been working with Edward Snowden, releasing material on NSA and GCHQ spying activities. The judges presiding over this case accepted the detention was "an indirect interference with press freedom" but was justified by “legitimate” and "very pressing" interests of “national security”.

Snowden’s releases in part detailed how national security agents purposefully weaken encryption, the very things that allow someone to purchase an ebook online with some degree of security. Other releases document a total surveillance doctrine, one which allows state actors to read whatever you are reading.

Both corporate and governmental organisations routinely collect vast amounts of data on individuals (and therefore the connections between them) - echoing another era that attempted to provide total national security through spying on its citizenry.

Wolfgang Schmidt was a former lieutenant colonel in the Stasi – the German Democratic Republic’s secret police during the Cold War. For him, Snowden’s revelations are impressive - “So much information, on so many people,” he said. “You know, for us, this would have been a dream come true.”

“It is the height of naivete to think that once collected this information won’t be used,” he said. “This is the nature of secret government organizations. The only way to protect the people’s privacy is not to allow the government to collect their information in the first place.”

When what we freely choose to read is no longer anonymous, we can no longer freely choose to read.

.jpg)